Ecological coral reef restoration

Methods that restore ecosystem function and services.

Upwellings.

Upwellings are a natural process that bring cool, clean, nutrient rich water from the deep to the surface waters. Reefs near upwellings tend to be far healthier and more resilient than nearby reefs that aren’t in contact with upwelled water. We can simulate upwellings with underwater pumps that help reduce temperatures, deliver nutritional subsidies that increase resilience, and reduce the incidence of disease.

Nutritional supplements.

Many reef organisms, including corals, suffer from thermal and other anthropogenic stress, which disrupts metabolic processes and requires additional energy to maintain health. Reefs with greater availability of food sources are better able to cope with changes in the environment. Supplementing reefs with extra nutrition gives organisms more energy to withstand change, improving their overall resilience to anthropogenic stress.

Soundscaping.

The role of acoustic cues in larval settlement of reef organisms is now well established, and these may play a role in maintaining communities more generally. By playing the sounds of healthy reefs underwater, scientists have been able to encourage larvae to settle on degraded reefs, potentially increasing their populations without any other intervention.

Transplantation.

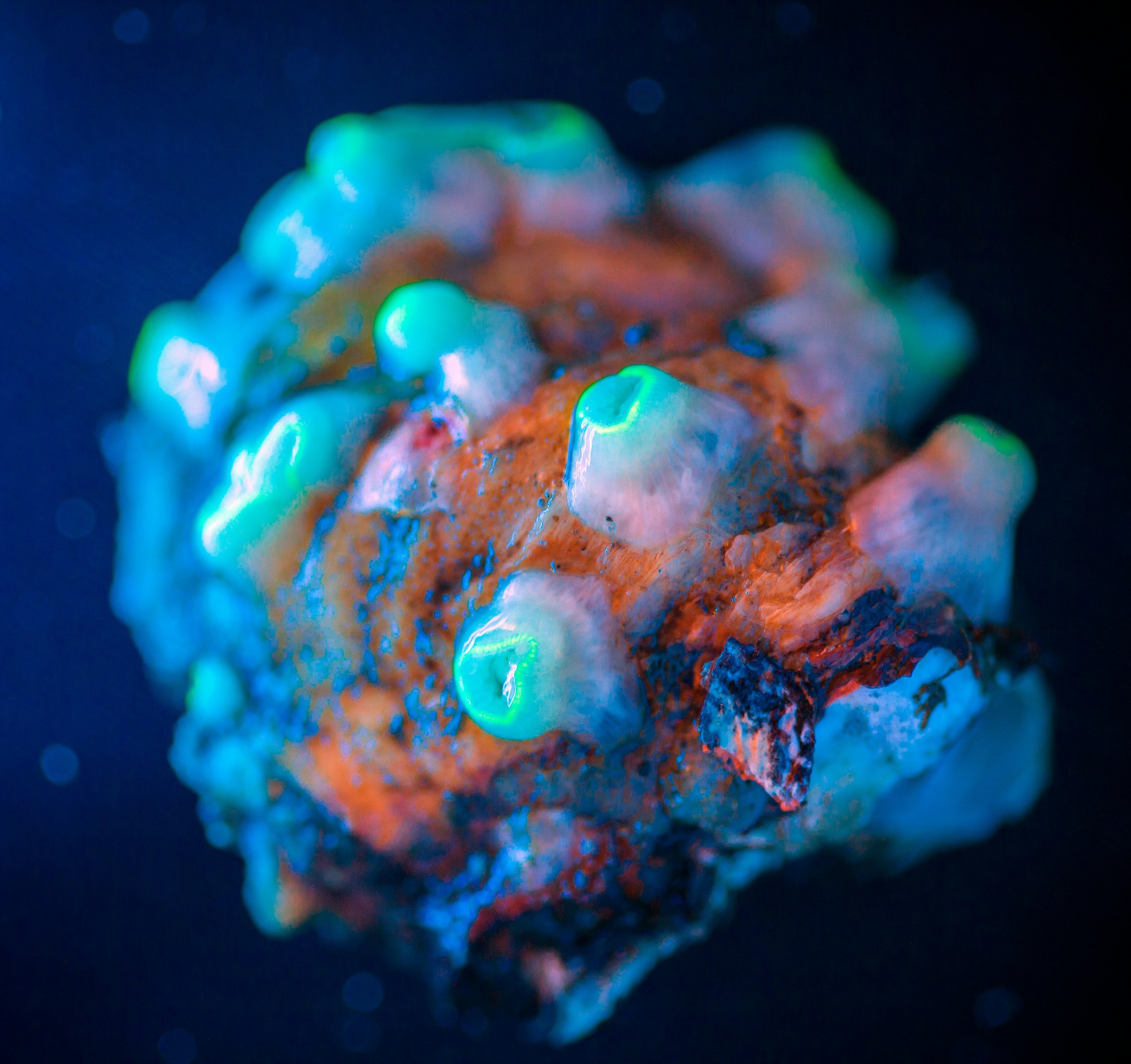

Promising new studies found that rearing corals on a healthy reef and transplanting them to a degraded reef produced higher invertebrate and healthy bacterial biodiversity with reduced physiological stress in the transplanted corals. Transplanting reef organisms from healthy reefs to degraded reefs can help improve the health and resilience of corals and coral-dependent organisms, and potentially nearby organisms as well.

Enhanced fertilization.

Enhancing fertilization by collecting coral gametes, allowing them to fertilize while in their native environment until they are functional larvae, and releasing them onto reefs has been shown to increase settlement rates by 100x. This approach drastically improves the odds of repopulation, and may also provide the benefits of transplantation as corals from healthy reefs can improve the health of their surroundings.

Reef connectors.

Many reef organism larvae spend time in the water column looking for a place to settle and grow, and this is a key process in preserving and expanding ranges and genetic diversity. Longer distances between reefs reduce the potential for larvae to settle on nearby reefs, especially when the density of organisms has decreased from mortality, reducing the potential for these processes to occur. By creating artificial reefs that connect distant patches of reefs, we can encourage the genetic movement of larvae, helping to repopulate and expand the ranges of healthy organisms.

Traditional methods.

The best methods to apply to any given vulnerable reef depends entirely on the traits and dynamics of that reef, and the resources that are available for restoration. While we aim to optimize for implementation efficiency to maximize positive impact, in some cases, labor intensive approaches to counteract anthropogenic effects like removing algal overgrowth and culling invasive (e.g. lionfish) or harmful species (Crown of Thorns starfish) are the most effective choice.

In cases where physical damage has occurred to reefs, outplanting corals can be useful, but requires care to preserve genetic diversity and resilience to multiple stressors. Artificial reef structures can also provide habitat complexity to encourage natural settlement and recruitment in areas where physical damage has occurred, but if systemic stress caused degradation to begin with, neither of these approaches will meaningfully restore reefs. Preserving natural resilience should be the primary objective of these activities, and they should be monitored long-term to ensure that natural patterns of succession and survivorship are conserved.

In all cases, controlling land-based wastewater, runoff, and pollution should be a cornerstone of any restoration program. As these developments are incredibly financially, logistically, and bureaucratically complex, we understand that it may not always be a feasible starting place for restoration. Wherever possible, our projects will provide support for reducing the amount of polluted water that reaches reefs.

Lastly, expanding and increasing protections for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) that reduce human pressure on reefs, particularly for fishing, and which are properly enforced, are an essential tool for the long-term conservation of coral reefs. We will support the formation and expansion of MPAs through the lens of environmental justice, for and with the communities whose livelihoods and sense of well-being depend on the health of their reefs.